|

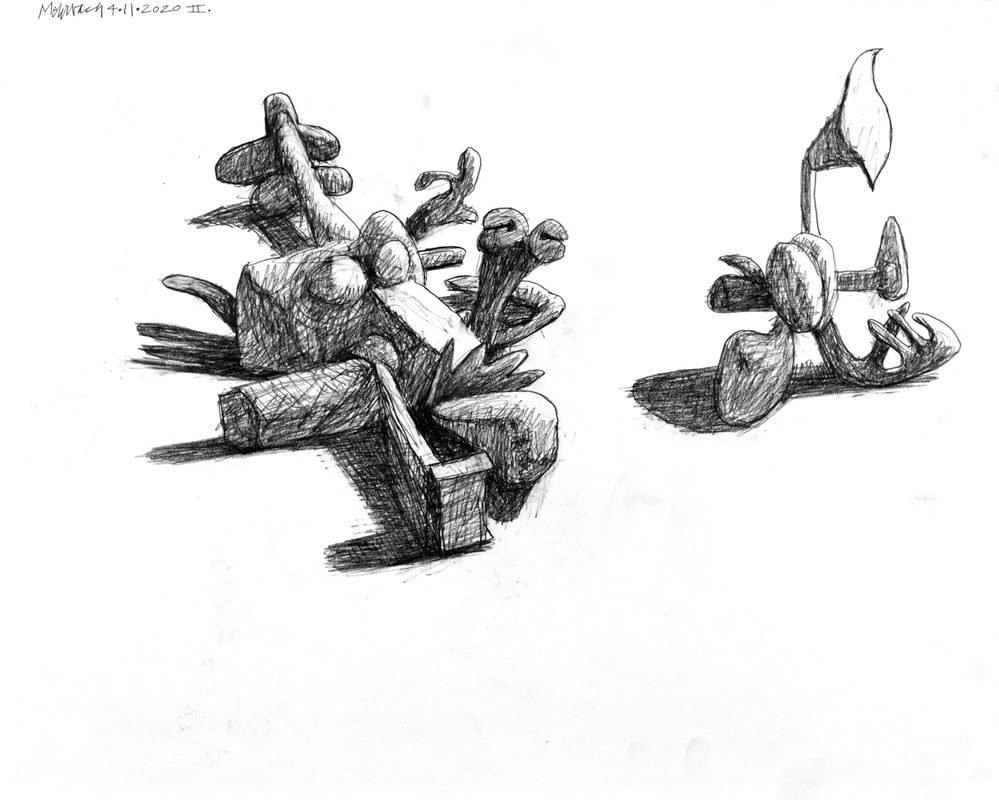

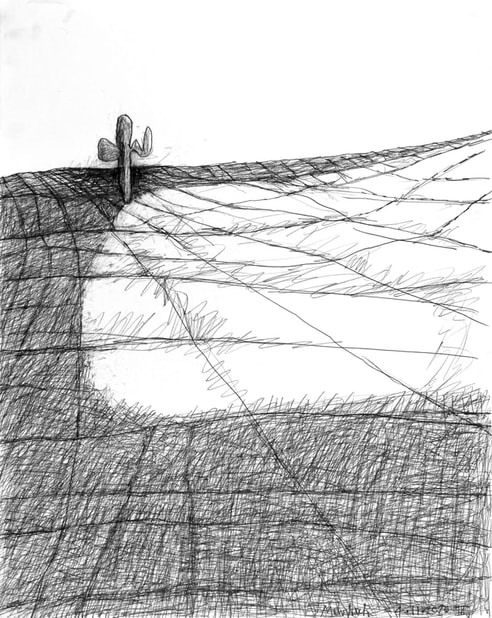

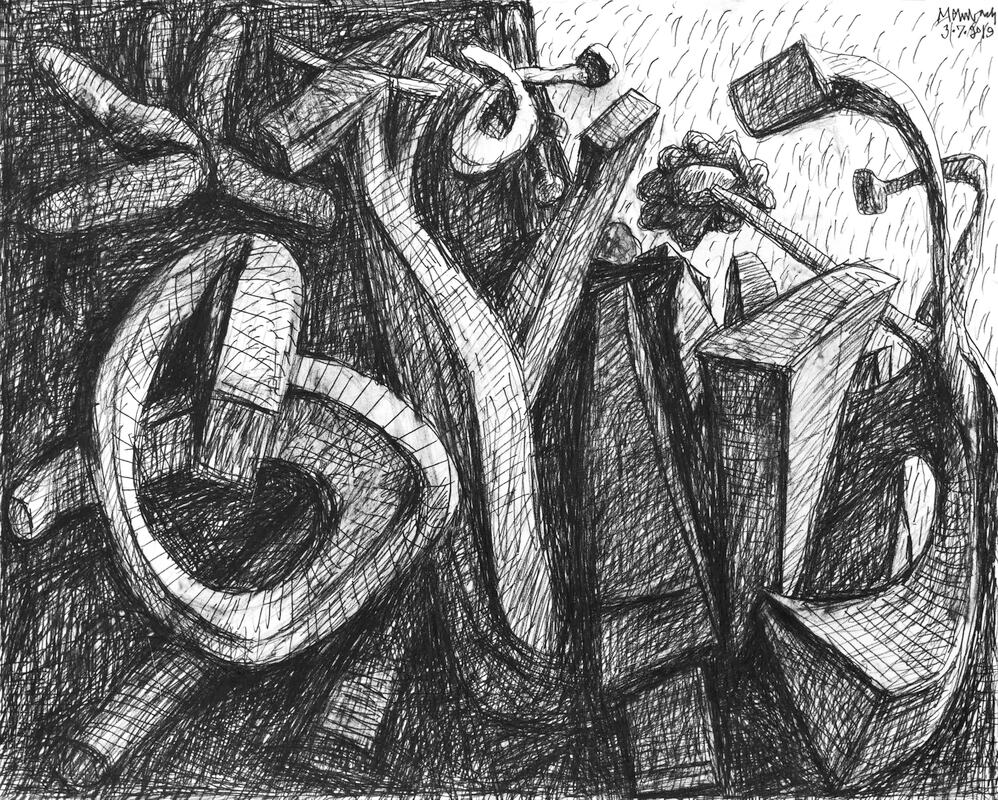

The world outside of my art studio is particularly scary; there is Covid-19; then there is the political manipulation occurring during, and around, the attack of Coronavirus. How will we, the United States, exit this time of worry, turmoil, and personal disasters? One of us who worries is Paul Krugman, the Nobel Prize winning economist (see below). I worry too, but I dedicate myself to art-making. I hope there are enough strong, able people in this country, who take Paul Krugman's worry seriously; I hope we come out of the 2020 elections toward more universal societal enlightenment. I make art. This is my primary concern. On my way, in this journey, I am comforted. I am hurting no one; I am swept away; I problem solving. Problem solving is similar to mediation. It is complete divorce from one's exterior. Thoughts, ideas, and memories, fully engage the emotions and the intellect. The world outside the studio is mute. The loudness that is me is centered in place, on a cement floor; I move back and forth to view, then mark paper (or canvas) with graphite sticks or pencils (or, in the case of canvas, I mark with paint). My body, my mind, become one in an endeavor to solve; I struggle to enlighten myself; I struggle to make visually real the thoughts and feeling I am having, moment by moment. This is me swept into knowing; this is personal presence. And thus, yesterday, I made three drawings. They are unique, one different from the next. This is me struggling to be free; these are me focussed, concerned with myself. I hope you also find value in these drawings. American Democracy May Be Dying

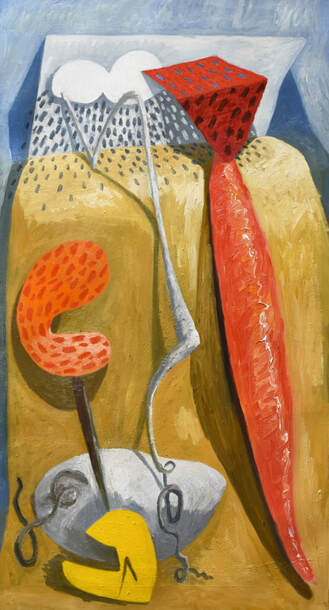

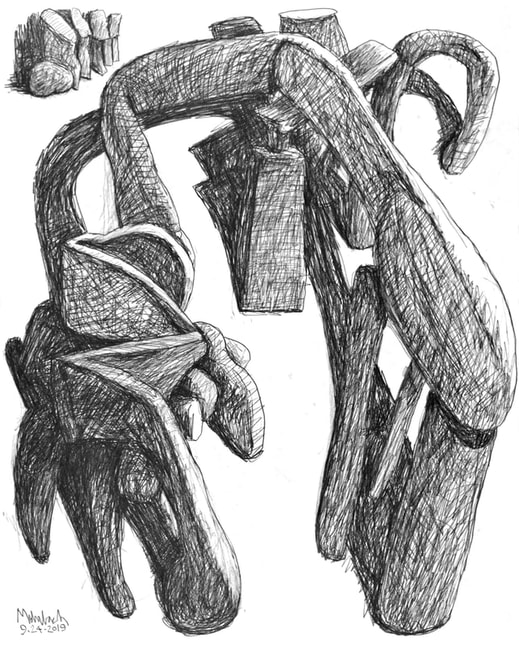

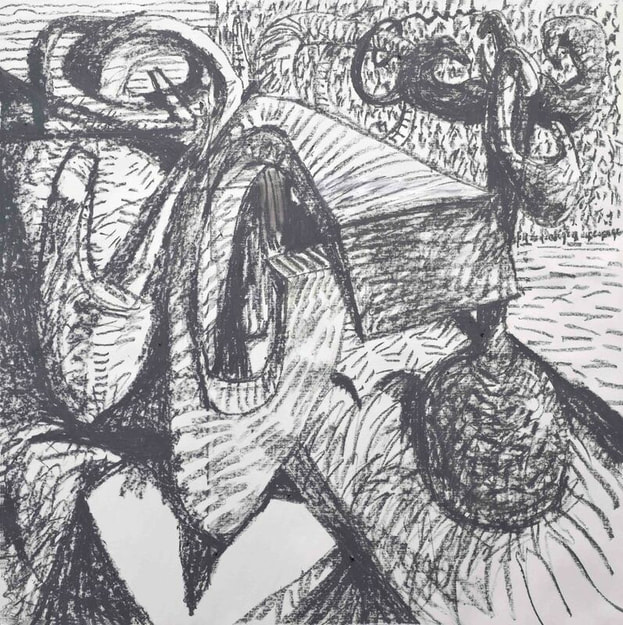

Authoritarian rule may be just around the corner. -Paul Krugman, The New York Times, April 9, 2020 If you aren’t terrified both by Covid-19 and by its economic consequences, you haven’t been paying attention. Even though social distancing may be slowing the disease’s spread, tens of thousands more Americans will surely die in the months ahead (and official accounts surely understate the true death toll). And the economic lockdown necessary to achieve social distancing — as I’ve been saying, the economy is in the equivalent of a medically induced coma — has led to almost 17 million new claims for unemployment insurance over the past three weeks, again almost surely an understatement of true job losses. Yet the scariest news of the past week didn’t involve either epidemiology or economics; it was the travesty of an election in Wisconsin, where the Supreme Court required that in-person voting proceed despite the health risks and the fact that many who requested absentee ballots never got them. Why was this so scary? Because it shows that America as we know it may not survive much longer. The pandemic will eventually end; the economy will eventually recover. But democracy, once lost, may never come back. And we’re much closer to losing our democracy than many people realize. To see how a modern democracy can die, look at events in Europe, especially Hungary, over the past decade. What happened in Hungary, beginning in 2011, was that Fidesz, the nation’s white nationalist ruling party, took advantage of its position to rig the electoral system, effectively making its rule permanent. Then it further consolidated its control, using political power to reward friendly businesses while punishing critics, and moved to suppress independent news media. Until recently, it seemed as if Viktor Orban, Hungary’s de facto dictator, might stop with soft authoritarianism, presiding over a regime that preserved some of the outward forms of democracy, neutralizing and punishing opposition without actually making criticism illegal. But now his government has used the coronavirus as an excuse to abandon even the pretense of constitutional government, giving Orban the power to rule by decree. If you say that something similar can’t happen here, you’re hopelessly naïve. In fact, it’s already it’s already happening here, especially at the state level. Wisconsin, in particular, is well on its way toward becoming Hungary on Lake Michigan, as Republicans seek a permanent lock on power. The story so far: Back in 2018, Wisconsin’s electorate voted strongly for Democratic control. Voters chose a Democratic governor, and gave 53 percent of their support to Democratic candidates for the State Assembly. But the state is so heavily gerrymandered that despite this popular-vote majority, Democrats got only 36 percent of the Assembly’s seats. And far from trying to reach some accommodation with the governor-elect, Republicans moved to effectively emasculate him, drastically reducing the powers of his office. Then came Tuesday’s election. In normal times most attention would have been focused on the Democratic primary — although that became a moot point when Bernie Sanders suspended his campaign. But a seat on the State Supreme Court was also at stake. Yet Wisconsin, like most of the country, is under a stay-at-home order. So why did Republican legislators, eventually backed by the Republican appointees to the U.S. Supreme Court, insist on holding an election as if the situation were normal? The answer is that the state shutdown had a much more severe impact on voting in Democratic-leaning urban areas, where a great majority of polling places were closed, than in rural or suburban areas. So the state G.O.P. was nakedly exploiting a pandemic to disenfranchise those likely to vote against it. What we saw in Wisconsin, in short, was a state party doing whatever it takes to cling to power even if a majority of voters want it out — and a partisan bloc on the Supreme Court backing its efforts. Donald Trump, as usual, said the quiet part out loud: If we expand early voting and voting by mail, “you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.” Does anyone seriously doubt that something similar could happen, very soon, at a national level? This November, it’s all too possible that Trump will eke out an Electoral College win thanks to widespread voter suppression. If he does — or even if he wins cleanly — everything we’ve seen suggests that he will use a second term to punish everyone he sees as a domestic enemy, and that his party will back him all the way. That is, America will do a full Hungary. What if Trump loses? You know what he’ll do: He’ll claim that Joe Biden’s victory was based on voter fraud, that millions of illegal immigrants cast ballots or something like that. Would the Republican Party, and perhaps more important, Fox News, support his refusal to accept reality? What do you think? So that’s why what just happened in Wisconsin scares me more than either disease or depression. For it shows that one of our two major parties simply doesn’t believe in democracy. Authoritarian rule may be just around the corner. I had intended to go back today, into the studio, finish this drawing. This drawing is not dated, nor signed (it was made yesterday). Looking at this drawing this morning, I call it done. There is a freeform play about it; I enjoy it, so I will accept it.

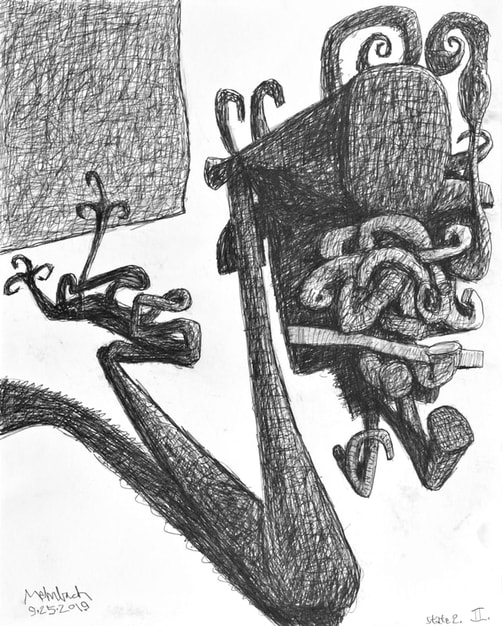

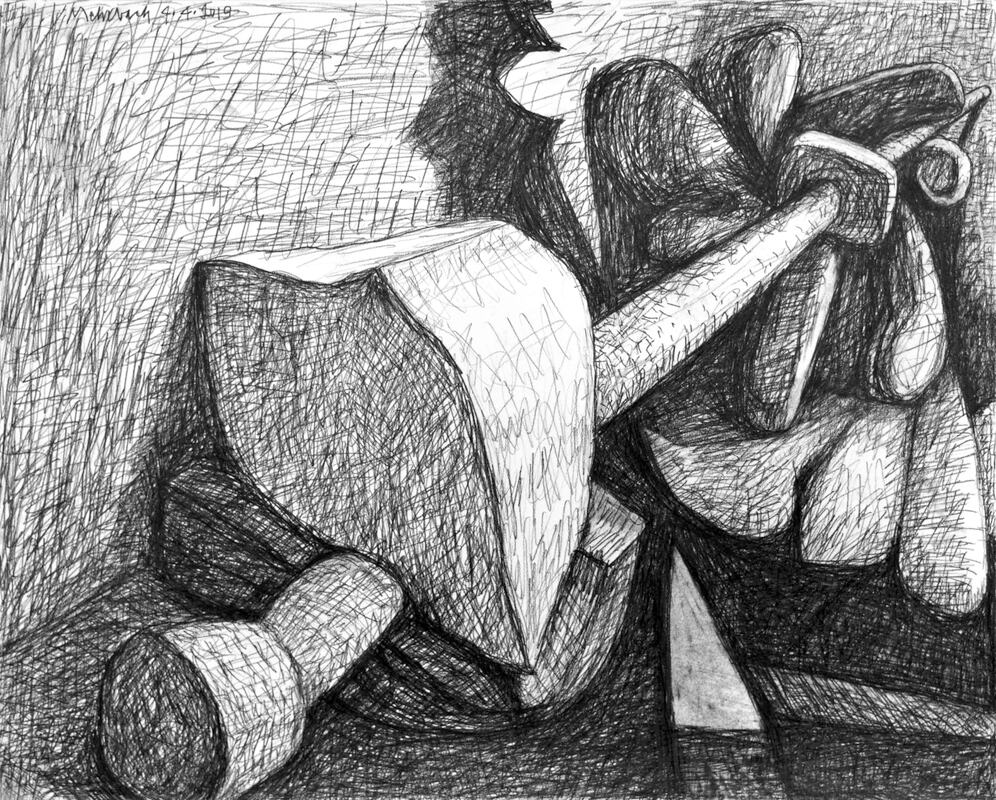

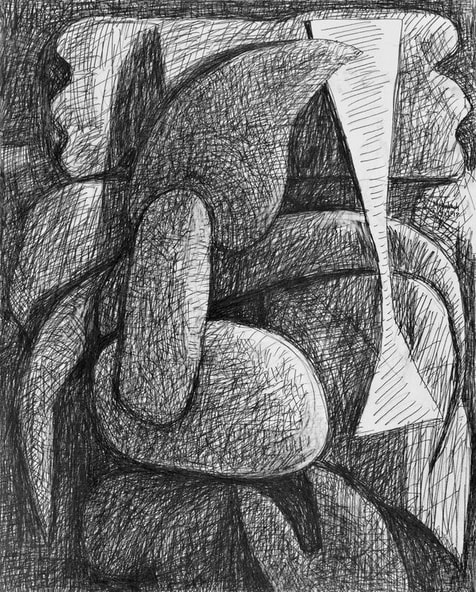

Today will be my first full day in the studio in quite a while. The Coronavirus outbreak has distracted me for many reasons. Today I feel fine. All my preparations, food, family, and friends, financial and shelter, feel comfortable. I feel a sense of security in this topsy-turvy world of disease and political missteps. This may not last. I will grab it while I can. I am off to my studio as soon as I place the period on this sentence. The largest hindrance to my success is my noxious ability to accept less than complete. You can see this happen in the second drawing I show today, but you have to go back to its original version to understand — see state 1 in this blog's post from 9/26/2019.

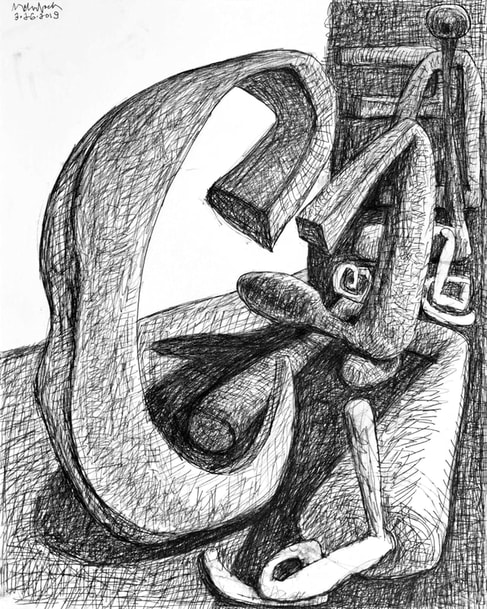

Yesterday's art-making felt wondrous, amazingly mindful. The drawing I made yesterday, from nothing but a white piece of paper, is one of my best. I lament my inability to reproduce it accurately, but that is nothing new. This drawing is new in its depth of confessional accuracy. My recent life has been much about reviewing & revising — a massive effort to determine reality by querying my past. Yesterday's drawing looked back to drawing No.2 in yesterday's post. This reviewing is more about method then art-work. Questioning methodological meaning is my current modus operandi. I stoled a form from "Drawing 09·22·2019 No.2" — It's that upside-down "U" that moves from bottom right, up and around, ending just to the right of my signature. Does it work? Does it have meaning? Is this a better drawing than the one from the day before? On it goes...

The biggest pain of living is lapsing into the pain that is time-driven. Acknowledging time makes one want to hurry. Time has an arrow that pokes holes in the present. Holes are absences. Nonexistence is the consequence. Here I am. I have returned to painting Doublethink. Doublethink is appropriately titled because my return brings the baggage of pent-up wanting. Doublethink is in a good place. It is re-educating me. I stepped into it, which is the most difficult part of the journey. It feels like a first step, but it is actually the third step.

As sophisticated as these drawings are... I ask, "Are these drawings too complex?" I fear they are too full of activity to be enjoyed simply and quickly. Do viewers enjoy wandering through drawings as abstract as mine? Perhaps a viewer would take their time to observe fully a drawing with many representational cues. I am not sure, so I worry.

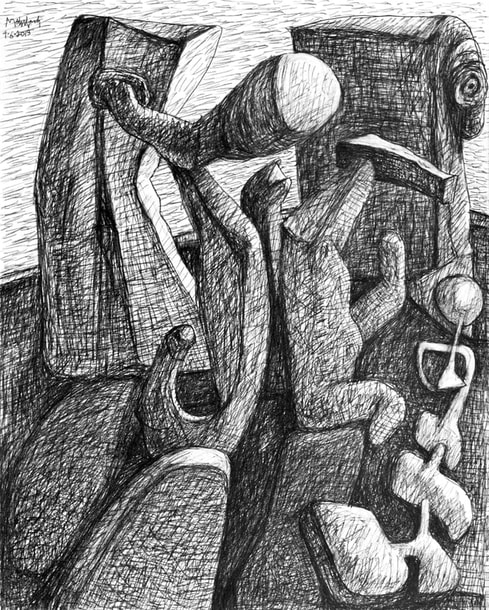

The bottom drawing on this page is in its second state. You can compare it to this blog's previous post to see the changes I have made. It is better. The movements within it are more obvious. I am trying to make my ideas more obvious to the viewer. I am hoping the viewer is engaged more easily, more directly, I working to draw the viewer in through instant involvement.  "How's It Gonna End" (2019 No.2, state 14), oil on canvas, 60x33 inches {"Life is sweet at the edge of a razor; And down in the front row of an old picture show the old man is asleep as the credits start to roll. And I want to know, the same thing everyone wants to know, how's it going to end?" -Tom Waits} Yesterday I left the studio in doubt, full of worry. Am I making exceptional art, or just stuff that will disappear as soon as I disappear? Longevity of an image is a test of its meaningfulness. James Joyce's "Ulysses" will be read as long as humans read. I want my work to sustain itself, I want it to give meaning and knowledge to generations of viewers. I want my work to give others an experience of real, authentic, satisfying, deeply human ideas, ideas to contemplate by the process of seeing. As I thought about my work last night it felt as if my work is difficult, introspective, and slow in comprehension. There was redemption within this doubt. I know I am constantly moving forward; I am consistently making better and better work. Better to me is defined as more profoundly adequate in its ability to say true ideas, ideas that all sensitive and intelligent people can see. I am optimistic viewers of my art will respond with satisfaction that is intellectual and emotional. I am working in order to touch all viewers with fullness of human capacity, i.e., the stuff that make us uniquely us. Yesterday I believe I took a small step in that direction; Looking here, at today's reproductions, my worries dissipate a little. Yesterday's work is good.

My methodology is more multi-think than Doublethink. This concerns me. I worry I see in a complicated and complex manner. I worry this makes it difficult to communicate through my art. Am I allowing myself to solve the needs of an image by multitasking the image? Instead, should I be simplifying my images toward their basic instincts? When I began the new painting, "Doublethink", I had ambition; I wanted restrict it to two contradictory and contrasting forms. Obviously this did not happen in state 1. You can see "Doublethink" as two contrasting areas; the left playing with rectangular in/out rotational vigor, the right with rounded up/down spinning-top-like verticality. I am not sure I will work on "Doublethink" again today. I need its complexity to percolate within/without me. There is a very complex drawing on my drawing board right now. It waits for me to solve it, to finish it off. I began this drawing with thoughts similar to those I began "Doublethink". My thoughts were similar in their simplicity-seeking. The drawing ran away toward a self-imposed complex solution. It feels self-imposed by the drawing, but of course it is me. It is me who is self-trained to see this way. This morning, in my effort to question my complexity, I purchased a sketch book. I hope it will help me resolve my issues with myself. I will use the sketch book to experiment with different ways to tackle by complex-seeing personality. I believe I am in need of simplification. I could be wrong.

"How's It Gonna End" (2019 No.2, state 9), oil on canvas, 59.5x32 inches {"Life is sweet at the edge of a razor; And down in the front row of an old picture show the old man is asleep as the credits start to roll. And I want to know, the same thing everyone wants to know, how's it going to end?" -Tom Waits} One day comes, I believe I know how to do this. The next days comes, I feel awash with more questions that are without easy answers. Nothing is obviously right or wrong. I wander as if in a desert. I am contemplating. I am alone. There is doubt. I am working. I am brainstorming. I am seeking. I find; I question everything I find. Am I being successful? I do not know. Such is the process of making-art.

Two days ago I believed I had made a breakthrough drawing. I tried to repeat the process. No two days, not two drawings, no two acts are identical. Nothing can be repeated. Each activity stands by itself. The path is evident; the next step lays before me, but the place I am going is not known. I accept this. This process is lively and mysterious. I trust it is worthwhile; I believe it will reward me with more: more knowledge, more ideas, more questions, more results. I will possess a lot of more!  "How's It Gonna End" (2019 No.2, state 8), oil on canvas, 59.5x32 inches {"Life is sweet at the edge of a razor; And down in the front row of an old picture show the old man is asleep as the credits start to roll. And I want to know, the same thing everyone wants to know, how's it going to end?" -Tom Waits} When Alberto Giacometti reached maturity he perceived his struggle as no longer a problem of creation, but one of destruction. His struggle was one for purity and perfection. Giacometti commented his sculptures often became so thin that one more swipe with the scalpel would reduce them to dust. I paraphrase, but the meaning is clear. I have reached a point in my art-making which worries me. Purity and perfection are enemies as well as a friends. They drive me, but they also force me to ask these questions: Will I always fail? Will striving for perfection not allow me to know a work is complete? With each work I am concerned I will be left with only a confused mess. This struggle is artificial. I am alive and well. I will not allow myself to be pulled astray. My energy is relentlessly focused on accomplishing the correct image. Each work is different.

Yesterday's drawing appears with too many rounded forms. It is shallow with little three-dimensional animation. I despaired while making it. In this drawing I had pulled away from my recent idea that three-dimensional contrast is extremely important to my expression. Today is new day. Today I make a new drawing. I will react to my concerns, the problems I see in yesterday's drawing. Yesterday I left the studio worried about the painting "How's It Gonna End" (2019 No.2). I wondered if yesterday's vast reworking of this painting had gone well. Looking at its reproduction this morning, I believe it did move in a good direction. Phew! |

To read my profile go to MEHRBACH.com.

At MEHRBACH.com you may view many of my paintings and drawings, past and present, and see details about my life and work. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed